AI Literacy for No One.

The Administration’s Executive Order is an important signal that amounts to theory without a budget or mechanisms to get it done. Now it's Congress's turn; here's what they can do to save the day.

Before the November 2024 election, I co-authored and published a memo for the Federation of American Scientists Day One program on what actions a new Presidential administration could hypothetically take to prepare students and teachers for a world of AI. I worked on the draft with several great collaborators, advisors, and education researchers in CS, STEM, and EdTech to help sharpen the focus. It was also based on a full year I spent working across Federal agencies to research emerging technology education, major gaps in our K-12 system, and possible policy solutions.

In this hypothetical White House wish-list, we recommended a Presidential AI Challenge for students and teachers; state-based partnerships with nonprofits, industry, and philanthropy to invest in and modernize teacher preparation pathways; adding AI priorities to discretionary Federal grant programs in ESSA, the Higher Education Act, at NSF, and at the Department of Labor; and unlocking Apprenticeships for deeper AI-related up-skilling, all primarily focused on teacher training and preparation.

Then I saw many of these ideas, slightly tweaked, suddenly land in my inbox last Wednesday evening when I read the full-text of the recent Trump Administration AI Literacy Executive Order. It arrives on the heels of the President’s new proposed budget.

There are both important wins, open questions on details, and concerning risks in this landmark Executive Order impacting the future of K-12 education. It arrives amidst other policy decisions that will serve to directly undermine its goals if we do not immediately course-correct. The decisions that Congress makes on the education budget and other AI policy details in the next few months will determine everything for our students 5, 10, if not 20 years into the future.

This “EO-Review” is based on my prior Federal fellowship, research conducted for two white papers via the Federation of American Scientists on the issue, and what I have personally observed from leading a very interrelated national K-12 education effort for the past 5 years that has worked with 31+ states and countless other groups. I haven’t engaged in any direct conversations with the administration. If ever requested, we would try to help the administration with this critical long-term policy work. As the White House correctly observes, preparing our youth for the world of AI is critical for their economic mobility and our international competitiveness, especially those at risk of being left behind. As my colleagues at aiEDU observe, it may amount to our generation’s space race, if not wider-reaching than the impact of the first one. We really need to get this right at this specific point in time.

I also debated engaging in this conversation publicly whatsoever. 90% of our team’s work is state and local, which has been true since we hired a full-time staff, and it will continue to be so for the foreseeable future. DS4E has a firm commitment to building bi-partisan common ground on a very basic idea: in the information age, every student in the U.S. should graduate from high school data literate. Comfort with the basics of data enables students to effectively interact with, deploy, and interrogate the results of AI tools, as one piece of the AI-readiness puzzle. Basic data literacy also has many other benefits – from helping our students navigate today’s information overload online, to ensuring our country’s future top scientists don’t make basic correlation-causation or p-value mistakes, to aiding personal decisions like which college to attend after high school.

However, this policy vision could have significant impact—if supported in the right way from Congress and the broader sector. Here’s what I think is going right, and what might go wrong if not addressed.

Exec. Order Wins

Real action on AI & education:

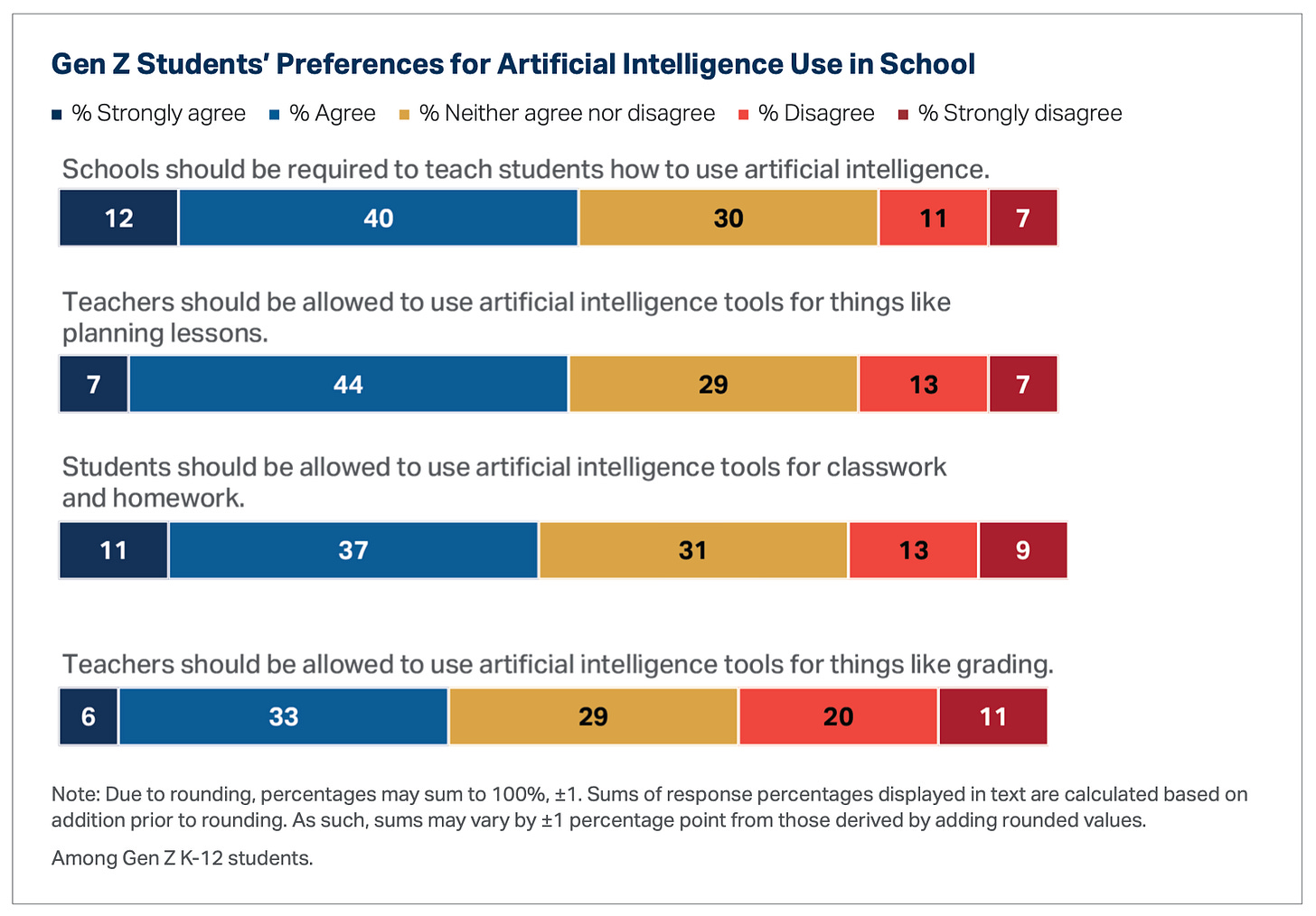

Both the prior administration and the Senate’s AI Insights Forum routinely missed education. Despite repeated advocacy calls for education to even be considered as part of national AI conversations, the issue was given little prioritization or meaningful resources. I was invited to two separate Biden White House convenings on AI education, and while both were important early steps, they were ultimately disappointing in face of the scale of our tech-literacy challenge and widening digital divide—with few new resources, grant programs, or even much publicity. AI skill-building in schools is both uneven and still too low overall, with both the computer science and data literacy skills to support deeper AI-readiness uneven by zipcode, race, and gender, while the most recent survey work shows AI skill-building is the top demanded consensus amongst students directly. Given the obvious international competitiveness impact of AI on our national workforce, this was a substantial miss, and this new Executive Order firmly changes that inertia and not a moment too late.

Clear priorities for K-12 and rural:

The EO states that “early learning and exposure to AI concepts not only demystifies this powerful technology but also sparks curiosity and creativity, preparing students to become active and responsible participants in the workforce.” I would also add thoughtful and engaged citizens to that list. The number of Americans in the general U.S. population that today incorrectly believe AI is sentient, two years after the mass public diffusion of LLM chatbots, is far too great for comfort. I also sincerely believe that neither the administration nor AI industry leaders want a generation of “digital sheeple” that blindly follow the recommendations of even the best AI tools. Given that only 49% of Americans complete any higher-education, which itself may change but only on the timescale of decades, we have a profound obligation to start earlier and go systemwide with basic technical skill-building and questioning habits, if not risk the greatest and fastest expansion of a digital divide we could possibly imagine. The call-outs to 4-H and rural education extension systems are also badly needed, given the profound integration of data and smart sensors into agricultural operations. Ensuring rural communities can access, benefit from, and understand AI (along with other emerging data-tech) is a priority our own team has championed for many years now.

Flexibility for local stakeholder collaboration:

Top-down guidance from the U.S. Department of Education on AI can only be so helpful to school leaders. Even as a former Department employee, I found the on-the-ground impact of 70-page PDFs to be quite limited for any person actually operating a school. In the U.S. education system of today, policy that moves the needle for education leaders happen near the ground locally, tailored to a specific state context. While centralizing research findings and exchanging successful practices across communities is critical and needed, and the Department undertook serious efforts to do so, the report-style vehicles through which we previously socialized this work were more often self-congratulatory than responsive. This EO moves us in a helpful direction for local communities to design policy with everyone needed at the table across sectors (hopefully better answering the “AI for what end?” question, which I suspect is very different based on where you live and what most people do). I sincerely hope there will be a process for state groups to communicate between one another at the national level and with the EO’s inter-agency Task Force. Inter-state communication will most definitely become a critical gap if we continue to erode national education infrastructure and do not have alternatives identified. I also hope those groups will be representative of a wide swath of people and sectors locally – not just OpenAI sales representatives.

Exec. Order Risks

No school leader can add new programs right now:

While the E.O. is a promising first-step, it is virtually impossible for any school leader to add any new program or learning priorities on AI basics anytime soon (this also goes for data literacy, financial literacy, civics, computer science, etc). School and district leaders are facing a perfect storm of 1) a post-ESSER funding cliff** 2) flip-flopping commitments on Title dollars, which would be the precise extra 10% or 20% of a budget allowing a school to allocate other revenue to new things 3) pressures from the administration, including potential investigations or funding cuts on a range of culture-war issues are placing demands on district leadership and contributing to increased turnover among superintendents and principals, that were already high to begin with 4) in some places, the possibility of law enforcement involvement, which irrespective of your policy preference on immigration or student advocacy can be a disruptive presence in schools, impacting the learning environment and diverting focus from education. This EO may become a tiny blip that school leaders easily ignore, because the administration has created these other conditions by choice. The collective impact has distracted the field from a focus on student academic learning, just when our education system is still recovering from pandemic-induced learning loss, and just when we need to become more competitive on the world stage. Nor can AI be a fix for any of these realities overnight; its implementation as a tool for school management or instructional-enhancement requires thoughtful design and a profound amount of management time to avoid backfiring, as LA Unified learned the hard way.

**ESSER funding shifted over time to support long-term student and instructional priorities through 2024. With the administration cancelling all ESSER spending extension requests, these areas are at greatest-risk:

A massive student-data-grab:

As a technical data expert that often believes data privacy fears can go too far (because the general public does not appreciate the significant anonymization in large-n records or simple disinterest in any one individual’s website click amongst millions daily), I think there are some real risks here. The dark side of the otherwise positive flexibility and industry-alignment in the EO sets up a likely scenario for a hunger-games style race towards capturing the data of young people at-scale. Imagine if you were Apple in the year 2000, and instead of selling laptops to hook-kids early to macOS, you could instead learn everything about a young person in an automated way from an early age: their favorite school subjects, hobbies, aspirations, questions (or anxieties) about personal relationships, and everything else. Then imagine the opportunity to monetize that data. Brand loyalty has even greater and longer-lasting potential dividends with AI infrastructure models; and this game is already being played at the college-level. Yet the word “data” somehow does not appear once in the full-text of the E.O., which should raise questions. With such a setup and when repeated over time even for any well-meaning enterprise, I have doubts, even if the best-intended individuals are in the room. At minimum it’s a serious governance issue that is not yet addressed in the EO and needs to be part of the agenda for its recommended inter-agency Task Force.

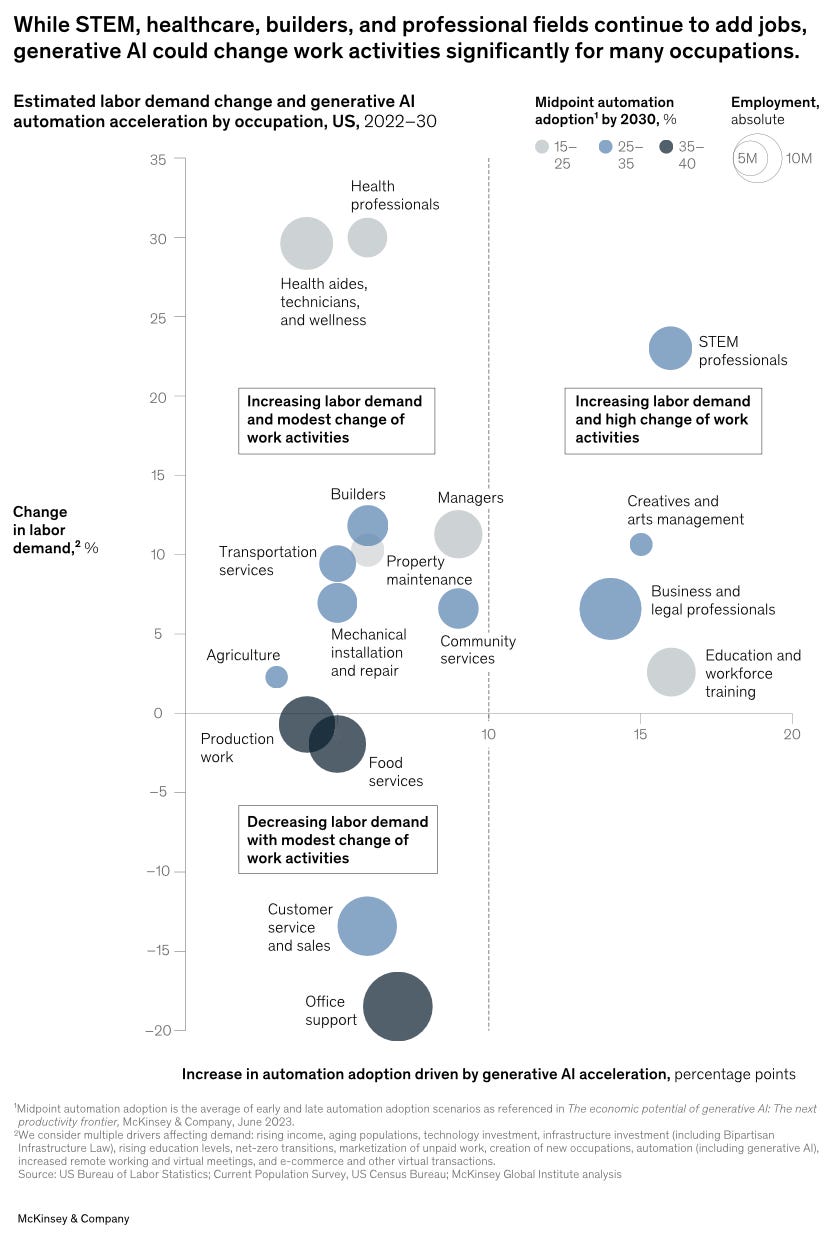

Apprenticeships for jobs that may disappear:

In the original white paper, the language on apprenticeships was very careful to focus narrowly on K-12 teachers (a career I do not believe will be automated any time soon due to relational and social needs for young people, a position that both an international teachers union and the WEF found unusual agreement on). The specific goal on K-12 teacher apprenticeships was to leverage existing Department of Labor funds and scaling models of state-level Grow Your Own programs that have gained significant success in in Tennessee and elsewhere, and were aimed at addressing the long-term teacher enrollment shortage. This is very different than an over-zealous embrace of apprenticeships for all careers in a world which AI may significantly change the underlying tasks within many jobs in short time periods. AI may also shift entry-level jobs the most, directly affecting Gen-Z job applicants. Across the board, we need to train students who can transfer knowledge easily and learn new skills continuously over time; not hunker-down on one type of present-day task and end it there. Without ongoing and permanent support for adult-focused retraining programs in the future, which have been typically ineffective historically when we tried them, I worry the enthusiasm for this approach could lead to dead-ends that we can’t yet predict precisely for any one career, but can otherwise very easily predict on the whole. This problem is solvable, such as finding ways to formalize skill-transfers between industries, shortening the development time of new apprenticeships to increase adaptability, or subsidizing work-based learning artificially in spite of entry-level automation. However, we need to be careful with the details and remain somewhat wary of any present-day labor-market predictions (like the one below from 2023, which can hide significant risks within sectors, such as paralegals within law):

AI for teacher evaluation:

While it’s a very small-line in the EO (sec. 7-a-ii), a colleague recently pointed me to this detail, and I have concerns. Leveraging AI to reduce the costs or even improve training at-scale is a very good idea and worthy research when complementing existing approaches. However, for teacher evaluation, AI models are only as good as the data they can collect and by which they are trained. The resources and physical infrastructure required to fully capture and convert the impact of a teacher-student interpersonal interaction to digital data, and then link that data to causal impact on academic achievement or lifetime outcomes is likely absurd, if not set to demand iMAX-Theater-level classroom equipment nationally. We could barely install new HVAC systems during the pandemic (which was one of the largest spend categories of ESSER funds). Poor proxies will instead be relied upon and create a new version of “teaching to the test” that is likely more dystopian, and could involve every student wearing VR Goggles or CCP-style cameras pointed at every classroom teacher in America. We have significant variation in teacher quality in the U.S. that requires a full suite of supportive and competitive approaches – likely something akin to high-knowledge professional-services like Medicine or Consulting. This seems like the worst approach out of the menu within a talent evaluation system that is already misguided conceptually, rather than one limited by its measurement tools.

No funded grants left to inform:

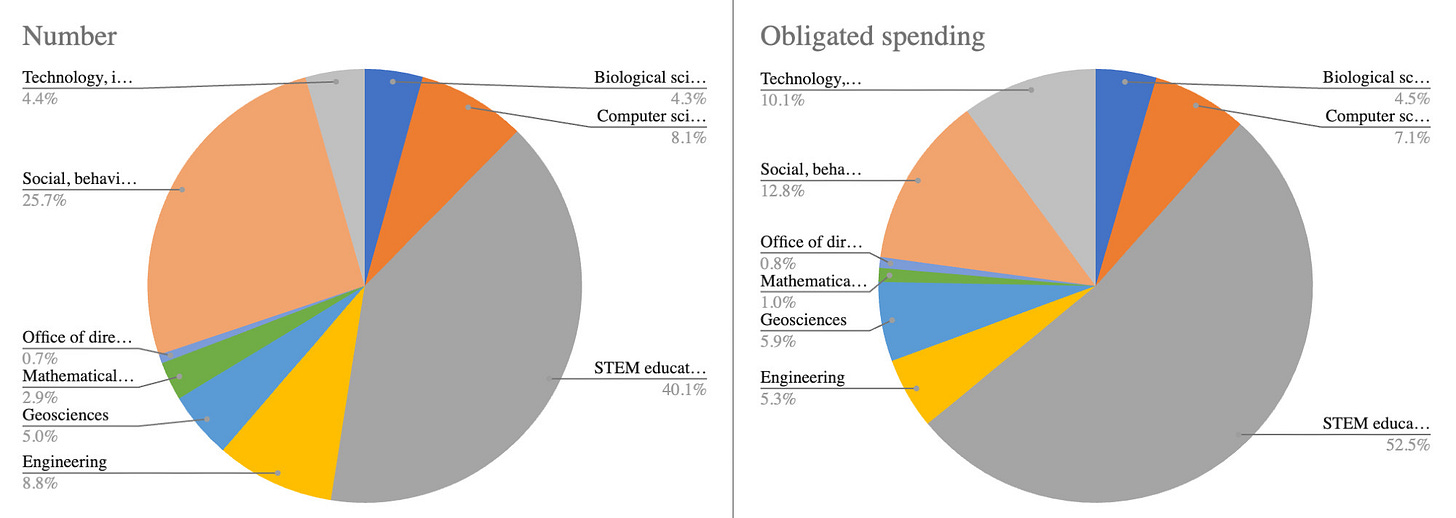

The E.O. explicitly integrates a new AI priority into Department of Education and National Science Foundation grant programs – programs that have historically supported teacher training through local partnerships or could enable badly needed education research to direct AI tools towards specific use-cases to benefit student mastery. However, these goals seem difficult to enact within 120 days given the administration also eliminated or substantially cut the same grant programs before the AI E.O. was even announced, has continued even more significant pare-backs since, and has proposed total cuts in the administration’s new budget. This includes national educator training grants critical for teacher preparation and addressing national shortages in classrooms, core K-12 research programs and research databases the field relies on for AI-related work, and the elimination of nearly all outside experts and staff who facilitate peer-reviews on new research. These cuts occur in a context where AI education experts are particularly scarce to begin with, have affected STEM education substantially more than other domains, and have lead to the cancellation of multi-year research projects directly focused on building models for student AI Literacy. Said another way, this EO is the metaphorical policy equivalent of bringing a small home-extinguisher to a raging wildfire—a wildfire for which you were also the original arsonist, motivated by a desire to see the forest managed differently. Meanwhile, China is investing in breakthrough methods to grow trees faster.

NSF Research Grant Cancellations by Category:

Take-Away: Congress needs to fund and improve this starter blueprint.

I am concluding with this one because it's the most important gap. The EO includes zero money to enact the vision that the administration outlines.

Congress needs to act quickly to support what is a generally constructive, innovative, and time-sensitive plan to ensure our students can compete in the global marketplace 10 or 20 years from now.

To give a sense of comparison, our team has been tracking the development of K-12 Data and AI education efforts in other countries for the past two years now. In countless examples, other countries provided new and additive public investment – sometimes orders of magnitude of difference even when accounting for relative size and wealth. For just one example, Scotland has invested $661 Million to establish themselves as the “Data Capital of Europe.” China has invested in the launch of AI degree programs at 150 colleges and universities as of 2023. Canada supported the training of 22,000 educators through the government program CanCode.

Taken together, the risks and unfunded mandate of the EO make an otherwise very constructive set of ideas a very excellent pipe dream.

We cannot cut Federal education funding drastically and also expect overnight success in preparing our young people for the greatest labor market shifts since the industrial revolution. There is no cake to be had after 100 difference slices are taken from the system, irrespective of the school model or level of Federal involvement you think is best long-term. We are simply moving in too many directions at once as other countries race ahead, leaving many of our schools with an empty platter and crumbs to spare over.

Our students will depend on us to knock this one out of the park. We have a narrow window to fix this.

All errors and opinions are my own, and do not necessarily reflect those of FAS, DS4E, or my co-authors.

Thanks so much for the thorough update and summary, Zarek.

My own district is in danger of being taken over by the TEA, (Texas Education Agency), which loves turning libraries into detention centers. So any waves I’m making about my data science course or training science teachers to use multiple linear regression and causal inference in their classrooms are getting drowned out.

As you point out, it’s hard to believe innovation is worth a damn when we’ve been bailing water for years. And that’s just state politics. The current national administration is gutting holes in a boat already taking on water, and then asking us to take the ship to Mars.